1914 Harley Davidson Similaria

-

I made this motorcycle to look similar to a circa 1914 Harley-Davidson. It had to be a functional rider capable of running 70 MPH with no strain and with robust electronics capable of powering electrically heated clothing. It took 20 months to build and when the dust settled I had made 195 drawings and 273 fabricated pieces. It has been on the road since August 2011 and as of 2025 it has logging over 19,000 miles. Starting with an Arlen Ness frame, a 1997 Harley Sportster engine (883 cc) was added. The forks were specially made by Paughco, 1” over. Night illumination comes from an original Ford Model “T” B&L brass headlight with a modern H4 headlight unit inside. The engine connects to the rear wheel via a belt drive (remember, the early motorcycles had leather belt drives). It’s a “hard tail” meaning it has no rear suspension. One can shift gears with the hand lever or foot shifter. The front fender “floats” with the wheel. I fabricated a fake acetylene gas bottle on the handlebars that houses the speedometer, tachometer, and indicator lights. Chrome has been eliminated from parts and most silver shiny bits are either nickel plated, aluminum or stainless steel.

-

I was born in 1950 and I saw, from time to time during my impressionable years, the 1910-1920 motorcycles on the road which had such a simple, elegant, graceful look.

-

My MISSION was to make a “Similaria” motorcycle at the intersection of form and function, where great attention would be paid to the details in every part. On antique motorcycles nothing is hidden and every part has a function. The eye picks up the distinctive colors of brass, copper, aluminum, and nickel. My goal was to make a similar motorcycle with that old look, but capable of running continuously at 70 MPH, with good brakes, good lighting, enough electrical power to use heated clothing, and “good to go” for the next 20,000 miles.

My GOALS were to go to the next level of fabricating difficulty from my last project (the “Yamaton”, making an XS650 Yamaha twin look like a Manx Norton). At the beginning of the project I found out to my surprise that this would mean making a pair of mirror image gas tanks and an oil tank, none of which I had ever done before.

What RESOURCES would be needed? I have a lathe, small milling machine, TIG welder, and other needed shop tools for bending, folding and mutilating fabricated parts. What I needed was time, money, raw materials, someone to weld the gas tank pieces after I tack weld them. (I could make all the welds on the gas tank but after thinking about the concept of 5 gallons of gasoline sitting between my legs while I’m going 70 MPH, my preference leaned to letting a pro make the final welds). I would also need someone to do the painting, powder coating, plating, and pin striping.

FEEDBACK on some of my ideas came from friends Ray S. and Doug H. Feedback on how I was doing time wise came from my time line schedule which was monitored regularly. Often I needed to make adjustments with time frames and add new activities.

Twenty months was a long time to keep one’s attention, focus, and enthusiasm for one project so I needed these 4 Guiding Lights to keep me moving.

-

Flat sided gas tank: The flat sides were a must not only because I liked the look but I also figured this would make fabrication easier because I would not have to form rounded pieces with compound curves.

Wheels: The same size wheels and skinny front and rear tires with close fitting fenders.

Headlight: A metal headlight with its Prestolite (acetylene) gas cylinder across the handlebars.

Hand shifter: A lever on the right side of the gas tank.

Foot boards: Rectangle shape.

Seat: A leather covered tractor style seat.

Handlebars: They must be wrap around handlebars.

Muffler: The round cylindrical shaped muffler.

Suspension: Springer front end, hardtail rear end.

Drive system: You can certainly argue that I should have a chain drive BUT first of all, the older Harleys did have a leather belt drive and secondly, with a 45 degree V twin a belt drive does absorb some of the vibration of the engine and, this being a rider, I wanted as pleasant a riding experience as I could get considering my comments above about suspension.

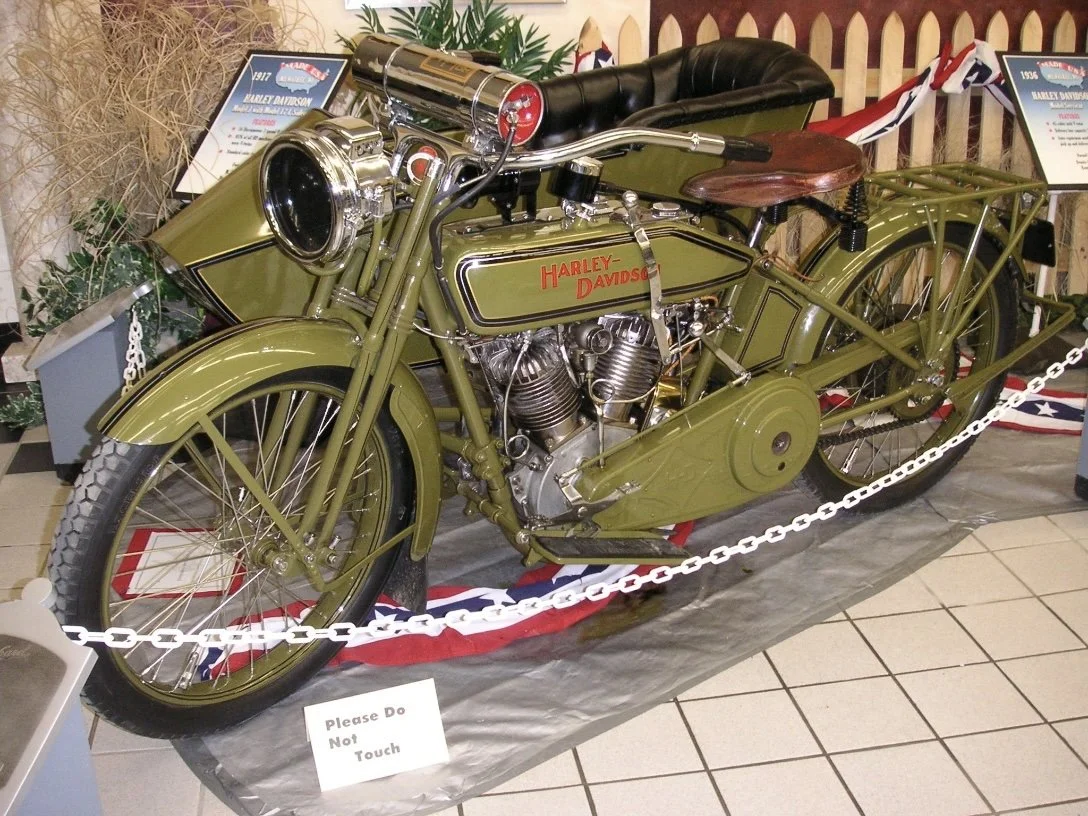

Bike inspiration

Bike inspiration

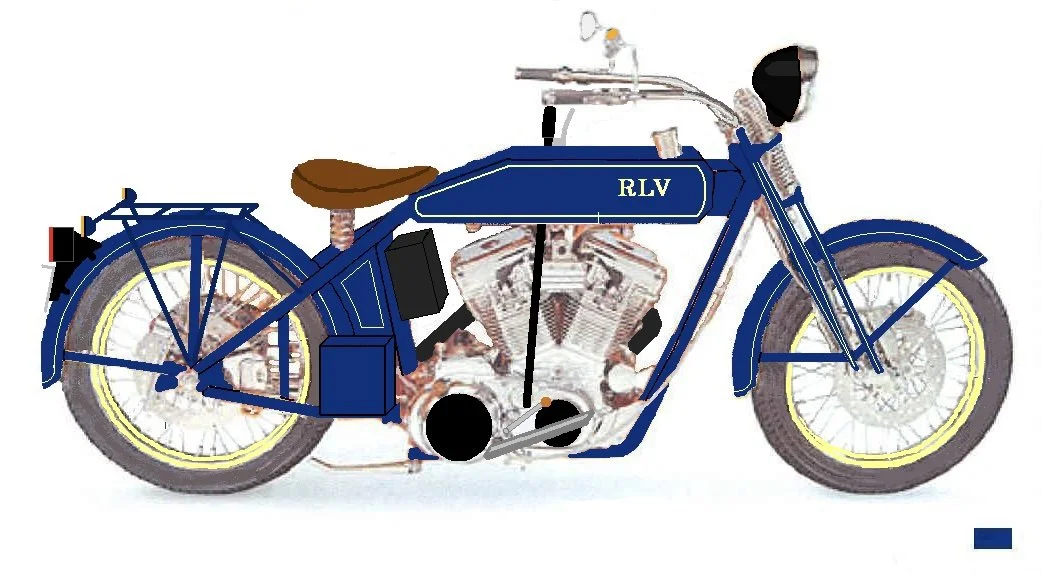

Arlen Ness antique style frame

Similiaria sketch

-

The engine choice was almost a “no brainer”. I wanted a 45 degree V twin and I did not need or want a big twin so the Sportster engine emerged as the answer. I have owned a 2003 883cc Sportster and I have also ridden the 1200cc version and I preferred the 883 due to my perception that it transfers less vibration to the rider. I wanted a 2003 or before because the rubber mounted feature of 2004 and later models, while more comfortable, became more complicated to construct with the rubber mounting of the engine with the attached exhaust pipes. On this rubber mounted engine the exhaust system is connected to the engine in its isolated vibratory envelope and not rigidly tied to the frame directly and I did not want to figure how I would mount that system with the Arlen Ness frame that was not designed for it.

-

The Arlen Ness frame was also the obvious choice for the frame. This was great news, not only because of my desire to use the Sportster engine, but also good news because that frame would make provision for the unique way in which the Sportster engine mounts to a frame. The rear of the engine attaches with 4 bolts to a relatively vertical plate on the frame which faces forward. To add to the good news, this frame was designed to give the correct alignment of the transmission’s drive pulley to the rear wheel’s driven pulley. The frosting on the cake was that the Arlen Ness catalogue also showed that they made the two mirror image flat sided style gas tanks that attached to each side to the upper frame tubes. They also made the oil tank.

Next step was to order the frame and get some confirmation on its suitability for my vision.Now I that I had the frame I gave the Arlen Ness folks a call to get the gas tanks and oil tank. That call revealed they no longer made any of the tanks! Oh boy! Was I up to the challenge of making them? I had not done that before. With further thought I realized these tanks had mostly flat surfaces and I did not have to learn the fine art of using an English wheel and a panishing hammer to form them. However I also realized that for the gas tanks, I needed to not only make two gas tanks, but had to make two exact mirror images that mated with each other where they connected to the frame. The oil tank would be a more straight forward fabrication being a basic rectangle.

I decided I was up for the challenge to fabricate these.

Oh I almost forgot, it was then time to get the engine.

SIDE BAR: My preference for all my builds is to get a complete running donor motorcycle and ride it for at least 500 miles before starting the project. This does three things. First, it gives me the assurance that the entire operating system is working properly or it allows me, if necessary, to make any needed changes or repairs BEFORE the build is started which saves me from making repairs around the newly painted/plated surroundings. Secondly, if I go to startup and ride the new creation and something does not work, I have some level of assurance that the parts I am reusing DID work when I put the 500 miles on the donor which limits the trouble shooting process to the changes and additions I have made. Thirdly, I save time by not having to keep picking away at swap meet after swap meet or on eBay looking for parts and hoping they function properly. The running motorcycle has all the parts needed to run. This approach has served me well but yes, there is certainly a price to be paid in dollars for this approach because buying a complete running motorcycle is definitely more costly than buying all the needed bits.

So I bought a donor motorcycle with only 4,065 miles on it.

I did ride it 500 miles and discovered the valve guide seals were shot which was subsequently easily repaired on this stock bike.

Work then began by removing the engine from the stock bike. All electrical attachments were disconnected along with the gas line, mechanical connections like the throttle and choke cables. Carburetor and exhaust were removed. The object was to get all things removed so that the bike can be rolled over on its side with only the engine bolts holding the engine in place. Then a bunch of wood blocks were cut up to support the engine such that it would remain in place on its side when the engine bolts were removed. Then those bolts were removed and the frame was lifted up off the engine. Then the new frame was lowered over the engine and bolts secured it in the new frame.

Next priority was to get this assembly supported by its wheels. The rear wheel was needed to be mounted with the drive line figured out. If a chain was to be used the alignment of the engine and the wheel sprockets needed to be figured out. The distance between these two sprockets is not so critical because chains are available in any length. However, as I had mentioned, my plan was to use a belt drive but these seemed to be available in a limited number of lengths. Fortunately Arlen Ness had this figured out with the position of the engine and the slots for the rear axle. I did make up some custom axle spacers to get the rear wheel and its belt pulley aligned with the engine’s pulley which put the wheel centered in the frame.

-

Next step was to get the front of the motorcycle supported with a wheel. Getting this figured out with the front end was a bit tricky. When I envisioned the style of gas tank I was going to make, I wanted its top flat surface to sit level when I got on the bike. If it sloped up a bit toward the front of the bike when parked that would be OK. What I did NOT want was to have it sloped down at the front in either one of those scenarios. With the more usual rounded gas tank tops found on most motorcycles this is not as critical because this angle is less apparent to the eye.

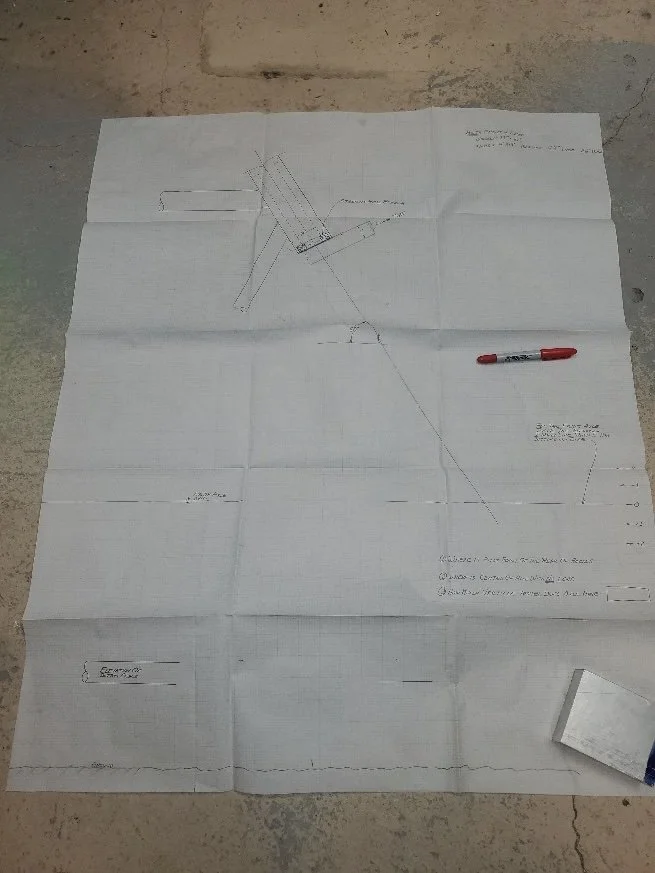

Also, to get this orientation one could usually tinker with the front forks as well as the rear shock. But here, being a hard tail, the rear frame height was established so I needed get the front end’s dimensions right. I wanted to use the springer style forks and Paughco made the style I was looking for in various lengths and they had the ability to custom make them to the length I wanted.

But what length did I need? Where is the length measured? That might seem simple but there were numerous variables. The fork sat at an angle. The axle sat at the front of a leading link. If the length measurement started at the top of the lower triple tree, how far will this surface sit below the bottom of the steering head? If the lower end of this dimension is the center line of the pivot where the leading link attaches, then how far up did the springs allow the axle to move when the frame is weighted down when I’m sitting on the bike? I made a full size drawing to help solve this.

Paughco was as helpful as they could be in answering these questions but I was getting the feeling that the only way to proceed was to buy the closest fit on their stock length options and go from there. Which I did. 2 inches over.

I fitted it up when delivered with the front wheel and tire and determined that I did need a custom length at 1 inch over.

We now had a rolling chassis.

-

Step one was to make mock-up versions of the tanks. These were made out of FloraCraft rigid foam that I bought from Michaels and they were repeatedly cut and trimmed until they had the shape and volume I was looking for.

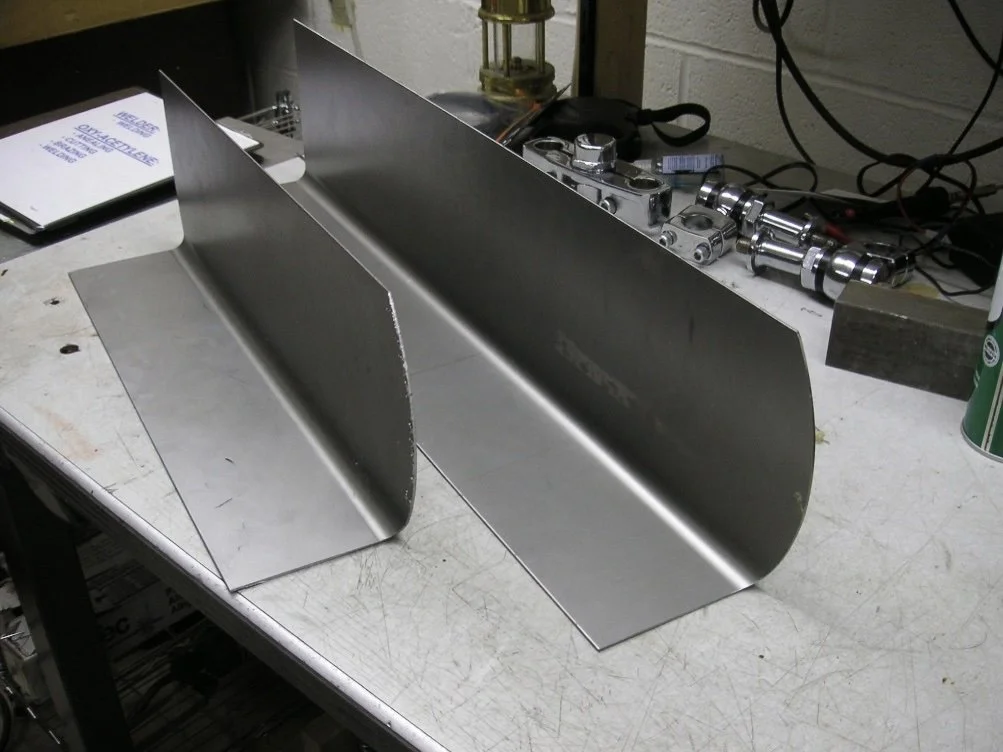

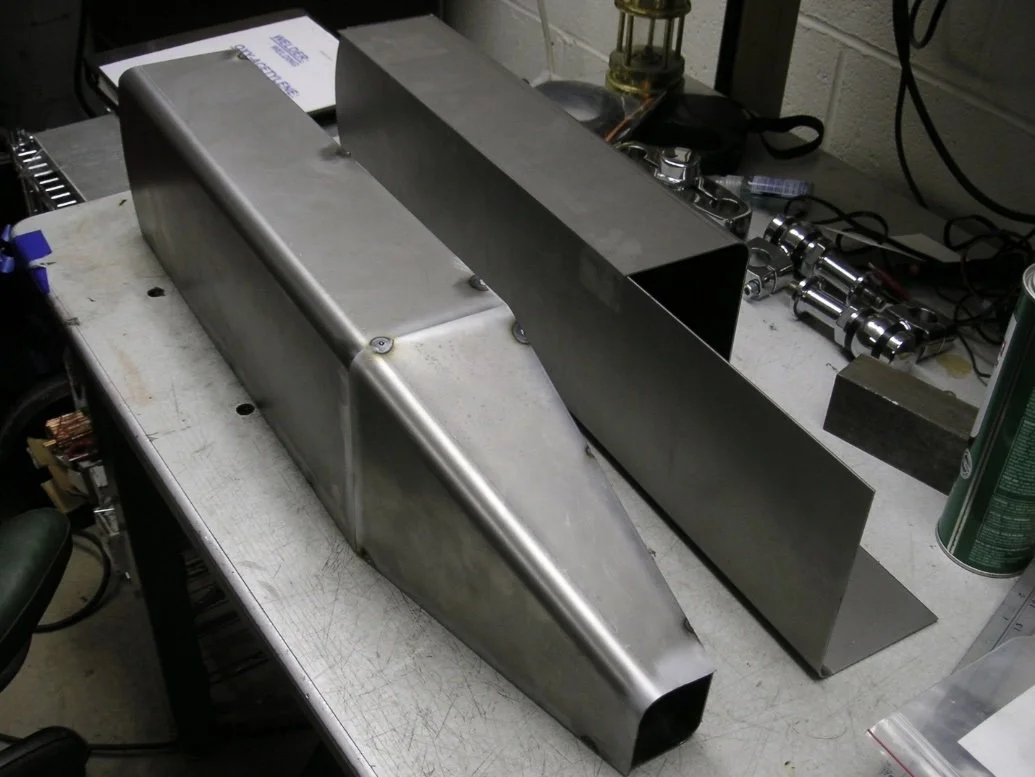

The top outside edges would have a “soft” looking ½ in. radius corner. So I went to a local fabricator who made four 30” long 90 degree angles with a 4”’ side and a 6” side out of 19 ga. steel that was .059” thick. They made the 90 degree bends with a ½ in. radius. The 4” surface would be the tops and bottoms and the 6” surface would be the sides. One of the real time consumers was performing the fitting work for making the sloped rear sections of the top and outside side that were angled “down” and “in” as it approached the seat area. Did I mention having to make TWO exact mirror image tanks? The rear end faces were flat plates but the front end pieces were hand formed at a 6“ radius to conform to the identically hand cut radiuses on the front of each tank.

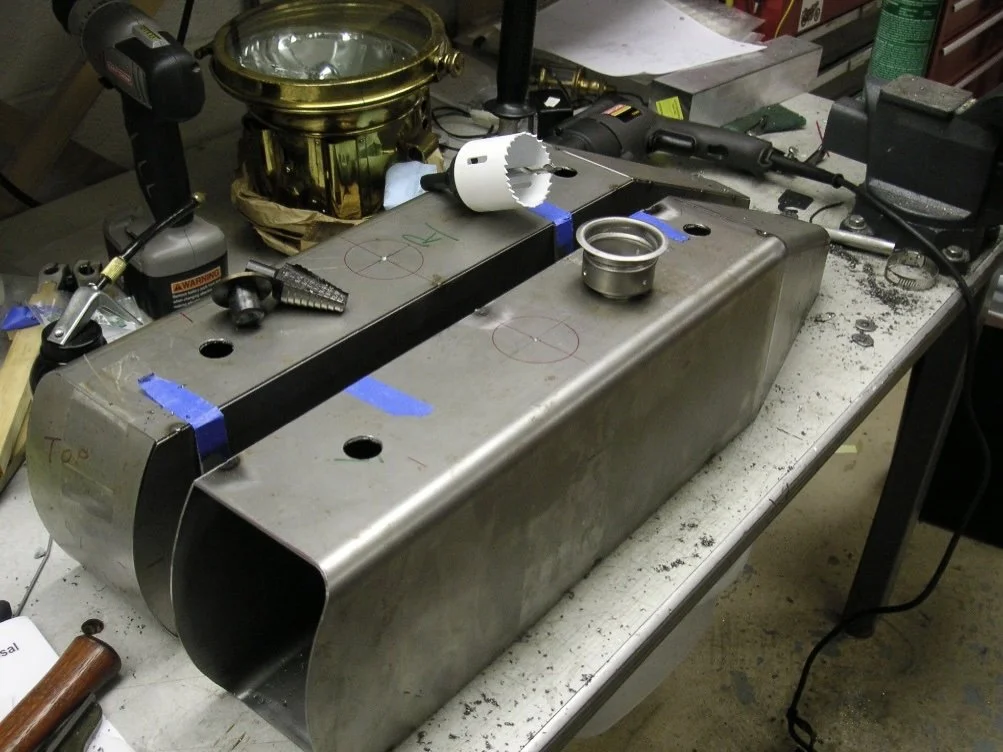

Then there was the design and fabrication of a mounting system.

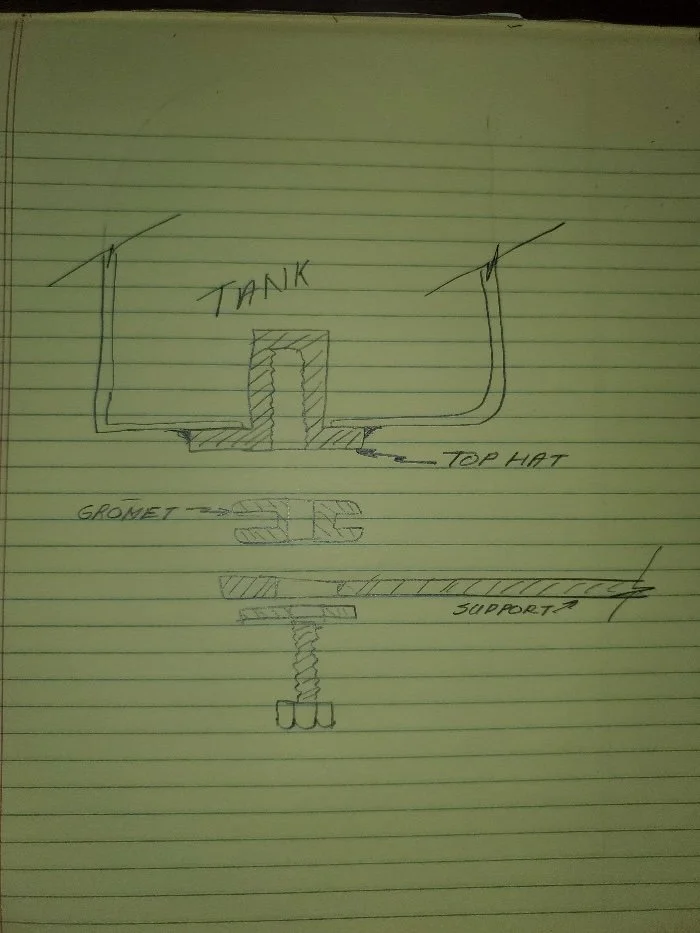

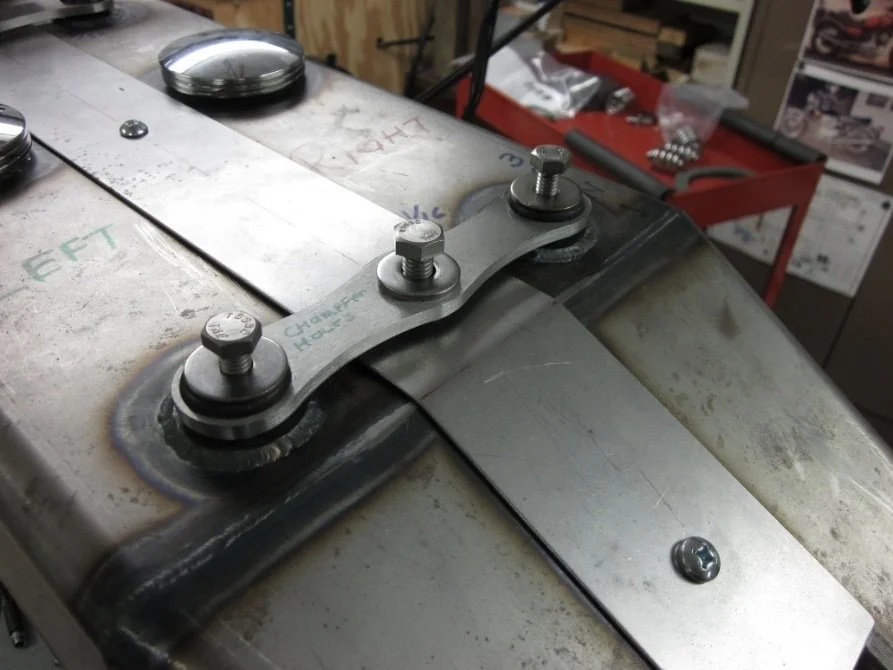

Referring to the sketch above, the system I came up with was to fabricate a top hat looking piece with a hole drilled into (but not through) the rim end of the top hat and tap it for a ¼-20 bolt. A hole was drilled into the tank and the piece was fit into the hole and the rim would rest against the tank’s surface and it would then be welded to the tank around the rim. What this did was to create a mechanical connection with the rim against the tank and the weld would seal the connection. Eight of these pieces were made, placing two on the top and bottom of each tank. The two tanks would be attached to the frame with four 1 ¼” x 6 ¼” x 3/16” steel bars that were made with holes at each end. I did not like the look of just straight bars so I set them up on the mill with a radius cutter and gave them a “waist” look.

Two of the bars were welded to the bottom of the lower top frame tube which would support the bottom of the tanks. The other two bars straddled the top of the upper top frame tubes and were welded in place holding the tops of the tanks in position. Large rubber grommets were put in the holes at the end of these bars. ¼-20 bolts were put through the grommets into the top hats in the tanks. The rubber grommets served to be a cushion for the tanks to sit on as well as helping to somewhat isolate the tanks from the engine’s vibration.

Holes for the filler caps and fuel taps were drilled in the tanks to accommodate the bungs for filler caps on the tops and fuel taps on the bottoms.

All the pieces were tack welded together. Was I going to do the finish welding on this? 5 gallons of gasoline resting between my legs going 70 MPH down the road. I don’t think that is a good idea so off the assemblies went to my friend and superior welder Lyle, for finish welding.

These tanks were mounted with brass bolts and washers.

-

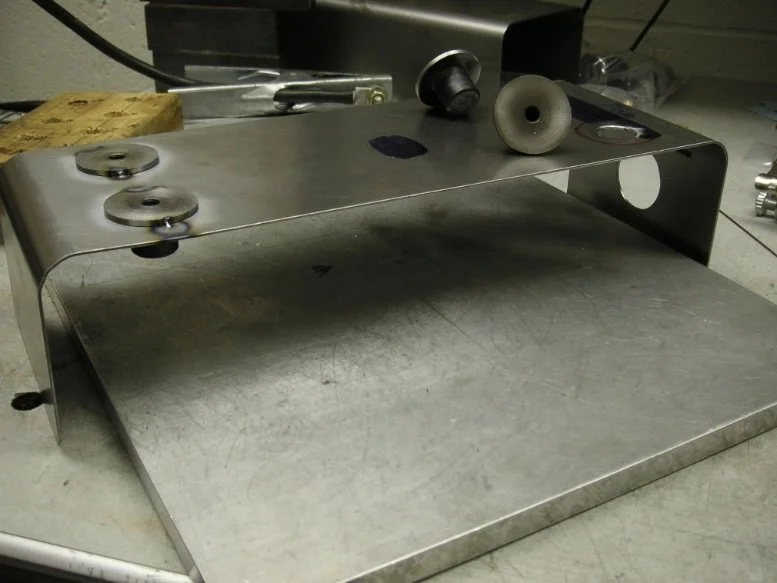

Like the gas tank, a Styrofoam oil tank was first made and put it in position which gave me some level of confidence in the size, shape, and location of the tank that I was planning to make. My design called for two main U shaped sheet metal pieces to make up the oil tank (see below) and they were also bent up with ½” radius corners by the same local fabricator that bent the gas tank angles. I drilled holes for the four mounting bungs (same as the gas tanks), the filler cap bung, the oil supply fitting and the oil return fitting and then tack welded these 7 pieces in position with the two main tank pieces. Then off they welt to Lyle for finish welding.

Frame

Engine

Engine

Frame and engine

Front end

Front end

Gas tank

Gas tank

Gas tank

Gas tank

Gas tank

Gas tank

Oil tank

Oil tank

-

WHEELS

The older bikes from the pre 1915 era seem to have the same size wheels and tires on the front and rear that were large diameter with thin tires. I chose to put on 19 in. wheels and run 4 in. wide tires. Somehow I did remember to make sure the front of the rear tire would not hit the frame. This meant using a relatively stock Harley Davidson front wheel and tire combination. For the rear, I acquired a front wheel rim, had Buchannan’s Spoke and Wheel make a set of corresponding stainless steel spokes that would allow fitment to the stock Harley rear wheel hub. I did also get the stainless spokes for the front wheel and my friend Bob V. laced up both wheels.

FRONT BRAKE

When it comes to brakes, I like good ones, real good ones!

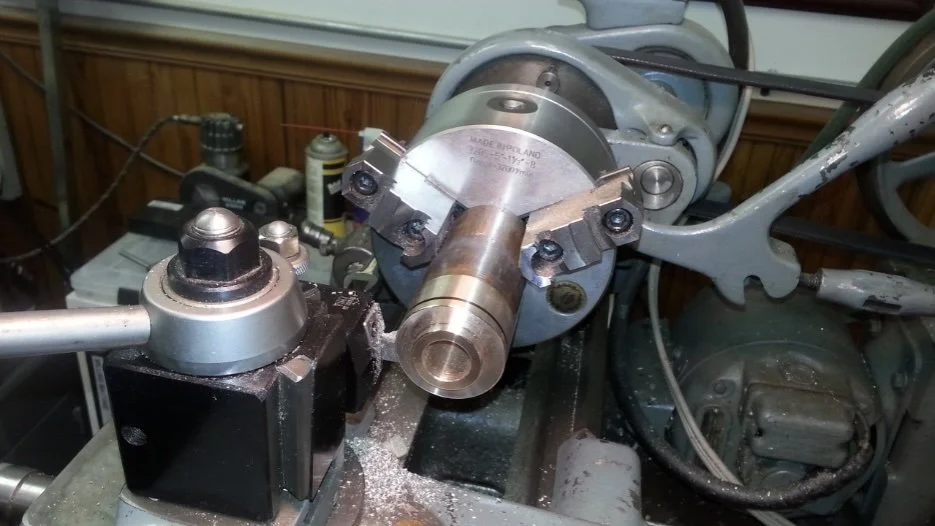

So dual disks were put on the front. The stock wheel hub has machined surfaces and a locating ridge for mounting disks on both sides but only one side has the five drilled and tapped mounting holes so I drilled and tapped the holes on the second side. The calipers are Performance Machine units that mounted on their carriers. I machined bronze bushings for the carriers to attach to the front axle.

Each caliper was flexibly anchored to the forks with a clevis at the carrier, a rod end at the fork and a threaded rod with a locking nut between them.

REAR BRAKE

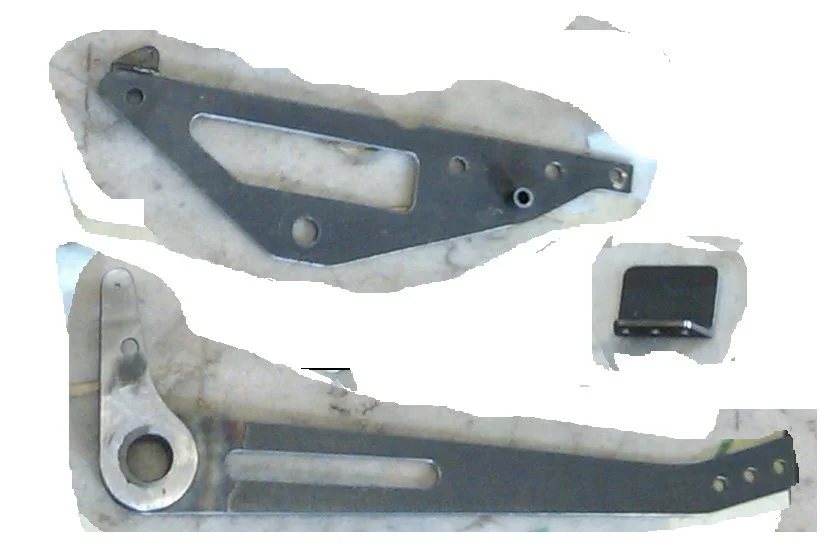

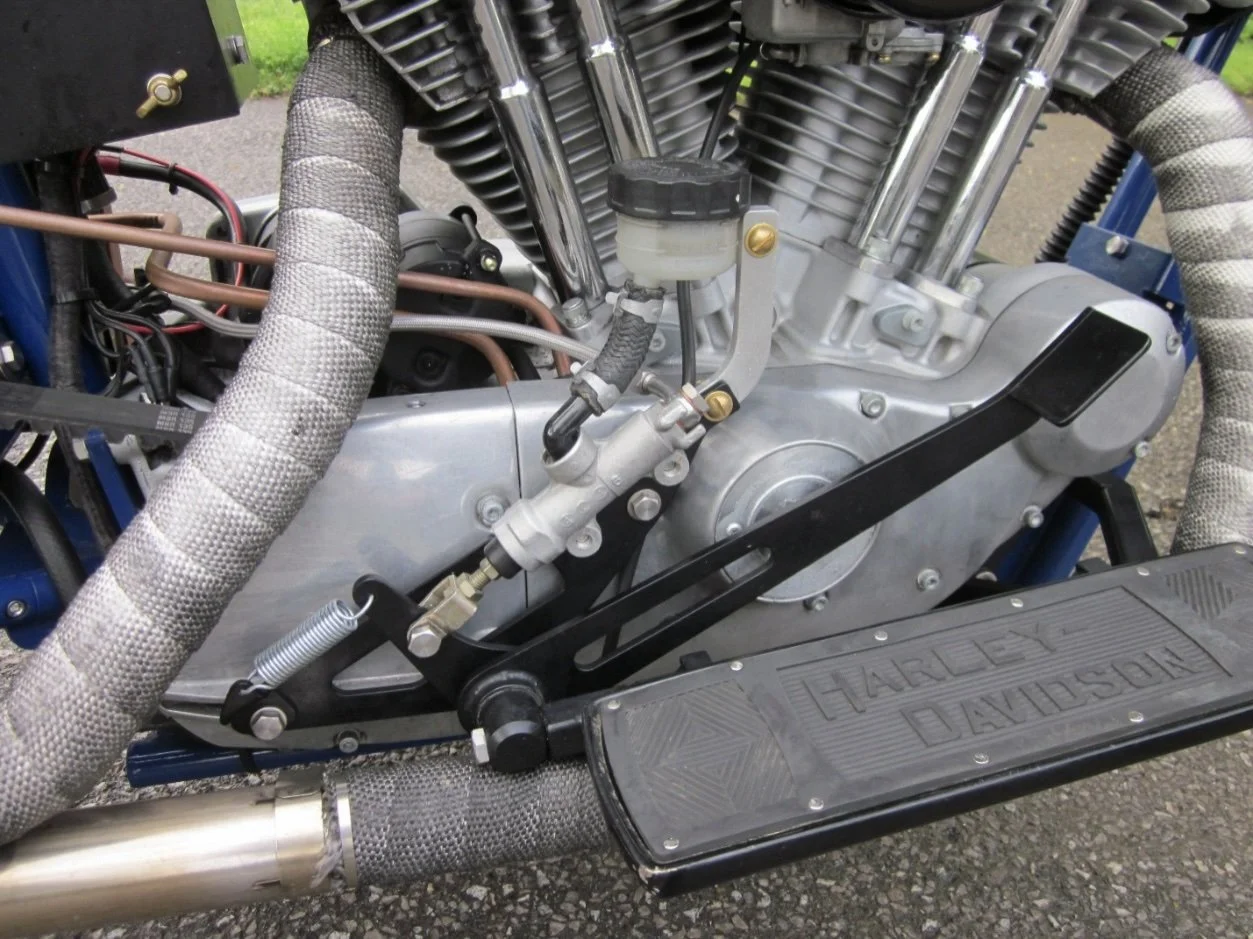

The rear wheel has the stock disk, but I needed to figure out how to activate it with my foot. The stock bike had a right side foot lever that pivoted on the same lug that the foot peg also mounted to. I decided to use that same pivot section of the lug for the pivot point of the new lever but there was the need to consider, design, and fabricate the following:

- Whose caliper to use (I chose a Performance Machine)

- What master cylinder to use with an appropriate diameter for the caliper (I used the stock unit)

- A foot lever with an appropriate length

- An arm to actuate the master cylinder and its appropriate length

- A mount for the master cylinder

- An adjustable link to the master cylinder

- A mount for the return spring

- An adjustable “stop” for the foot lever in its up position

- A mount for brake fluid reservoir

- A way to activate a switch for the brake light

Here were the solutions to all those considerations. First the disk, caliper and mounting bracket.

One must also consider how to mount the rear brake caliper and do so in a manner that allows the caliper to move backward and forward as the axle moves when adjustments are needed to keep the correct tension on the drive belt (or chain when used). A Performance Machine caliper carrier was used and I machined a billet spacer on the axle to push the carrier out far enough to the left so the two torque lugs would engage the lower frame tube.

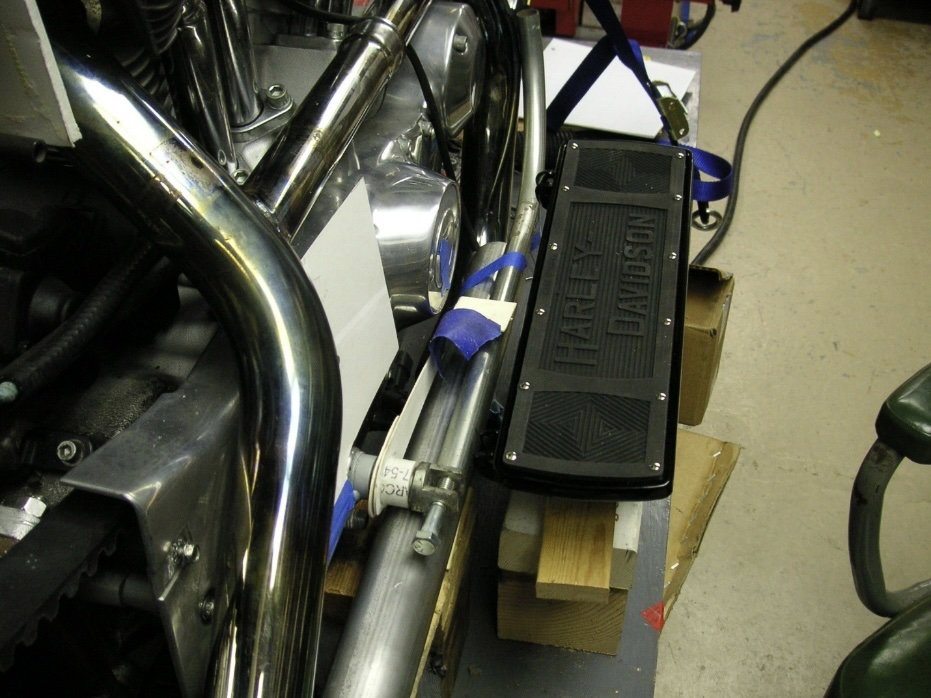

At the brake pedal end of this system, here is a picture of the mock-up pedal. I was solving how the exhaust pipe was going to interface at the same time.

…and figuring out how the foot boards would mount (see a later section of this write-up).

The backing plate to which the return spring was attached had to be greatly expanded to hold the master cylinder, the brake fluid reservoir and be configured so holes could be drilled to align with the two stock threaded mounting holes in the engine’s right side covers.

-

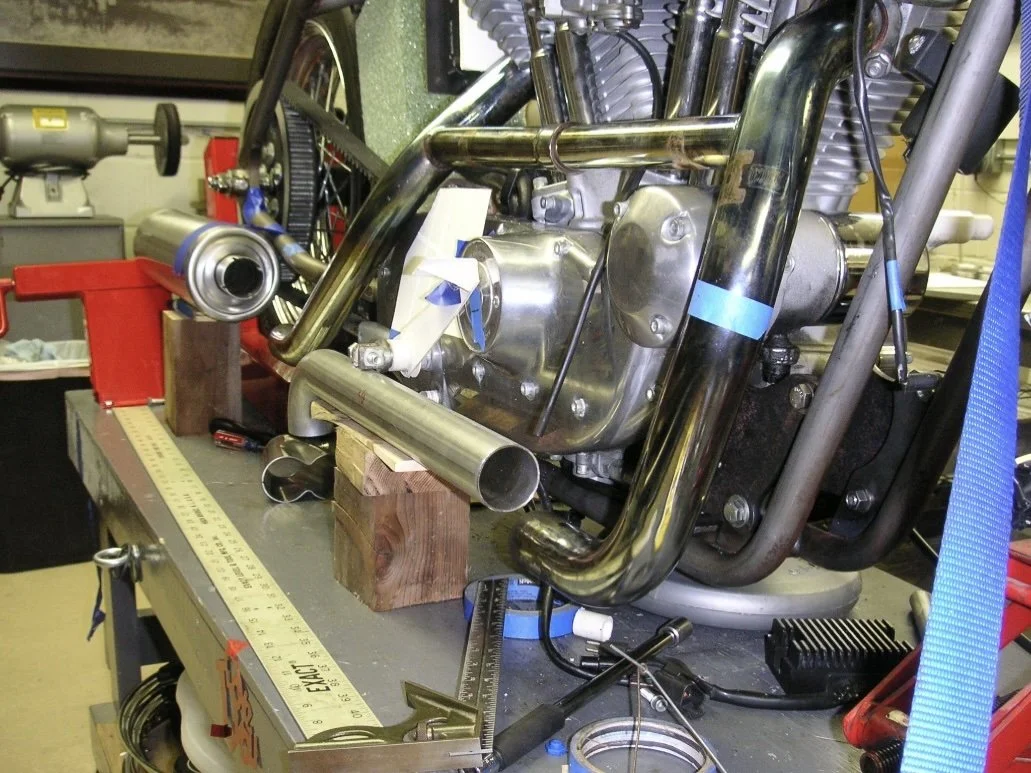

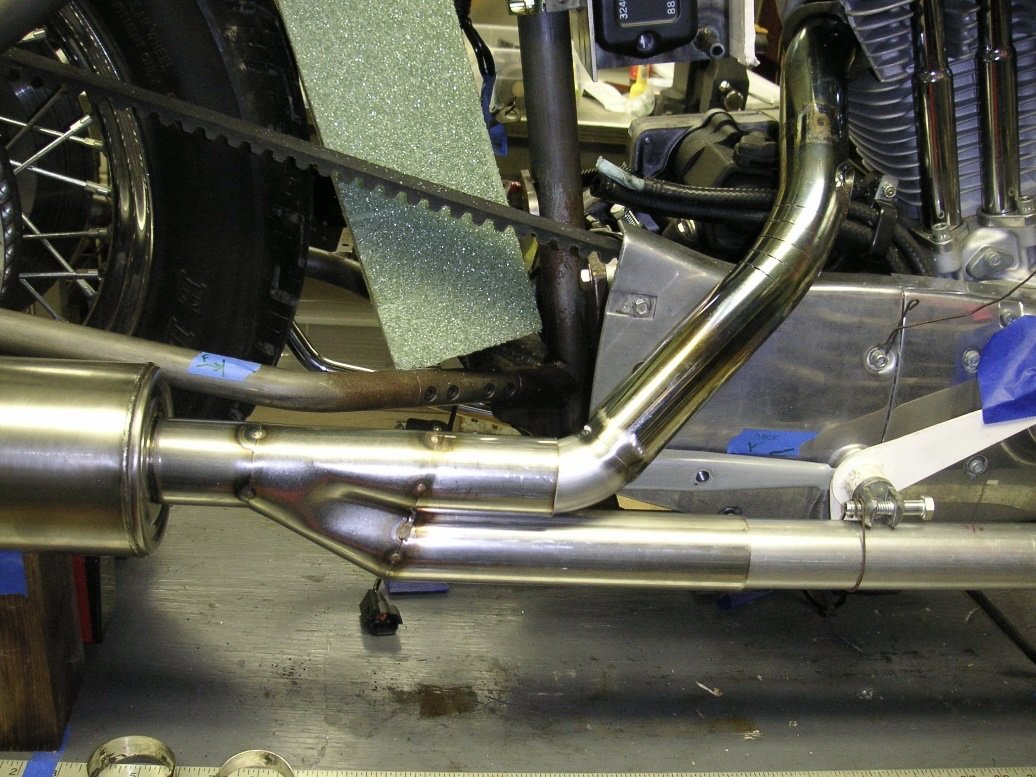

As Stephen Covey reminds us, I began with the end in mind. The muffler. What type did I want and where would it be mounted. Old school mufflers were generally just simple cylindrical shapes mounted in a horizontal manner. My vision included a 2 into 1 exhaust pipe that led into the muffler. The look would be something very basic, where function was the main consideration, you know, like it would have been in the 1914 era. I didn’t want a loud muffler.

Looking around, SuperTrapp offered the one that had the perfect look. The added benefit was the option for the number of exhaust disks utilized which offered tuning of carburetor jetting and sound level. The only modification needed (to the muffler anyway) would be to make the muffler exit tip go straight out of the back, not at an angle.

What followed was the simultaneous consideration of where/how to mount it with the ability of getting the two exhaust headers to the spot of connection with each other and then into the muffler.

I did have this going for me: on motorcycles with rear ends with shock absorbers, muffler mounting gets tricky because the natural place to mount it is at the swing arm but the arm moves up and down. But on this bike it was simpler because there was no swing in the swing arm, it was a rigid frame member.

I needed to get the muffler high enough to not hit the ground in a right hand turn and pick a location where I had a glimmer of a good chance of being able to connect it to the rerouted exhaust pipes.

SIDE NOTE: The complicating factors in working with round exhaust tubing are (in the least) three things: 1) most of the work is in a 3 dimensional world which makes every angle of connection incalculable, 2) the job of fitting the end of one tube which intersects the rounded side of another tube is quite time consuming, and 3) how to make bends in the pipe.

To the last point of making bends, the good news is that we can purchase premade 180 degree “J” bends in most all the needed pipe diameters for our motorcycle exhaust systems. These can be cut to make bends less than 180 degrees.

I started placing the exhaust components in different positions to get a sense of what might work with the motorcycle in the riding position. Blocks of scrap wood laying around the shop provided the staging until I thought I had it right.

The piece of horizontal exhaust pipe was propped up where I thought it would be mounted. This is another one of those tricky items of priority of design and fabrication because the foot board location also needed to be simultaneously figured out which was in turn dependent on where the foot brake pedal could be mounted. I have already covered this foot brake mounting and at this point in the exhaust design I was utilizing a cardboard mockup of the foot brake pedal. Refer to the white bits in the picture below. That allowed me to envision the footboard placement and where it needed access to the frame for attachment which now allowed me to return to the exhaust pipe fabrication.

I was modifying the bend in the stock pipe by cutting gashes and bending it to where I thought the next joint will be.

Satisfied with that I put a minimal number of tack welds on the pipe. Remember the most successful people always have a plan B and I wanted to be able to easily cut the weld out and reposition if I needed to.

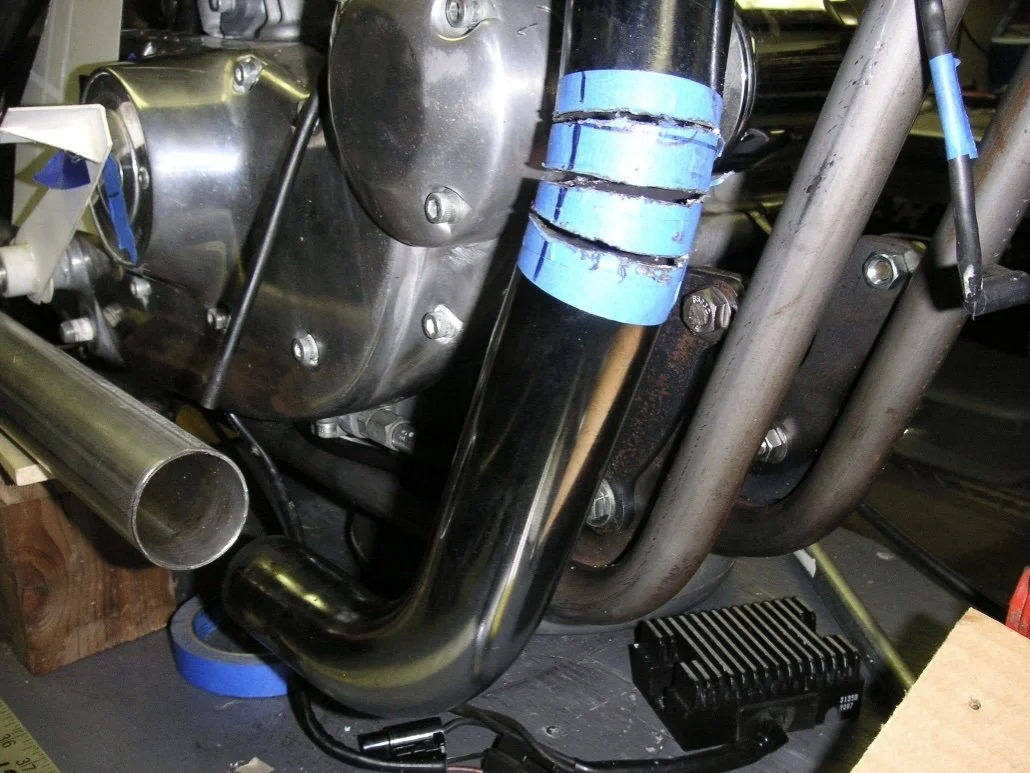

Next that lower curved section of the exhaust pipe was cut off and both ends of this section underwent the same filing and fitting process until the final fitment slowly, I mean very slowly, took place.

By this time it became evident that the cross over balancing pipe had to be abandoned and was subsequently cut off and the two remaining holes were filled in.

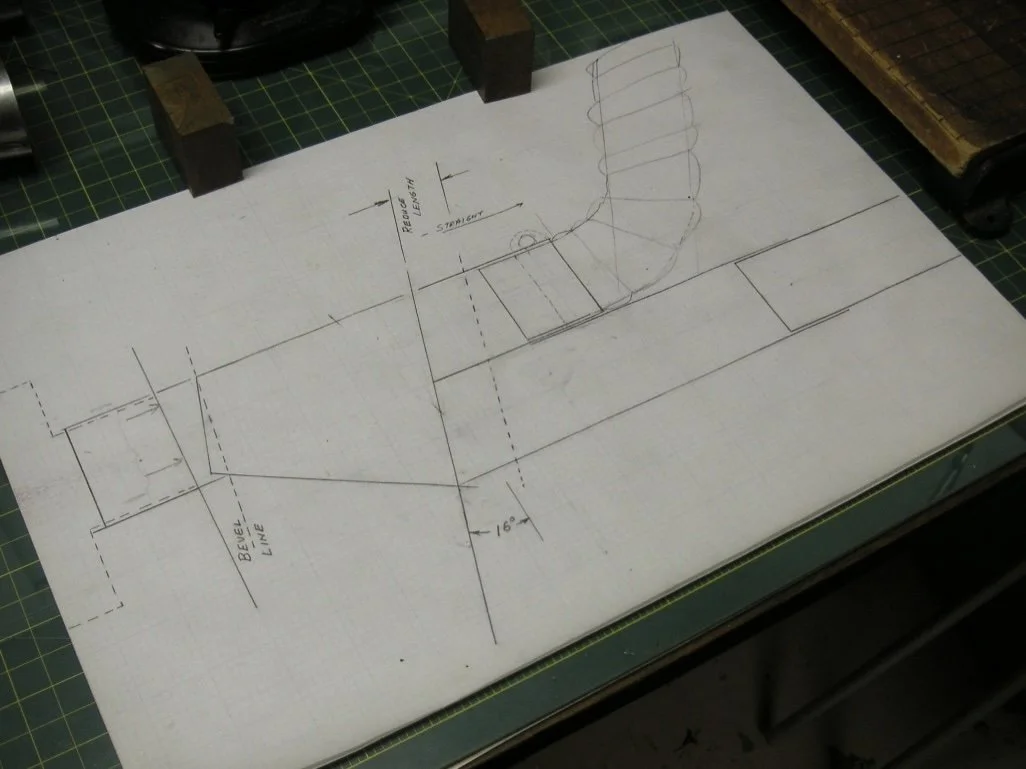

Now I jumped to the muffler’s connection and worked back to the front pipe keeping in mind how the rear cylinder’s pipe would connect. I wanted to design a “Y” connection that would 1) be constructed of pipe with an appropriate ID that will slip-fit over the two incoming pipes and 2) be angled such that the muffler could gain some ground clearance. In other words, the top exhaust pipe that came from the rear cylinder would have a straight through section and the front cylinder’s pipe will come up to meet it in the “Y”. A sketch ensued.

What followed was the long process of pipe cutting, filing angles, fitting, more filing, a little bending to get the faces to meet each other and then some tack welding.

OK, it was assembled and work began to bring the rear cylinder’s pipe into the “Y”.

Like the front pipe, the stock pipe’s bend was notched to get it in position and shortened. Another “J” bend pipe was used to fit up against the stock pipe and into the “Y” connector.

The final assembly was tack welded leading into the muffler. The two forward facing pipes will have clamps on them along with the muffler connection.Item description

Front brake

Front brake

Rear brake

Rear brake

Rear brake

Rear brake

Rear brake

Rear brake

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system

Exhaust system